For a long time, Japanese raku pottery remained a mystery to me. I like to make raku pottery, and I was aware that the techniques I had learned are western raku methods. I knew that these were different from the Japanese methods. But I felt a bit intimidated and ill-equipped to understand Japanese raku. However, recently I became intrigued and decided to learn more about this ancient Japanese practice. And this is what I discovered.

Strictly speaking, Japanese raku pottery is produced by the Raku family who are located in Kyoto. Raku ware started to be made in the 16th century. And there have been 15 established generations in the family producing raku. One of the most recent descendants of the raku family line is a potter called Kichizaemon XV.

Kichizaemon is the title given to the head of the Raku Family, at any given time. Kichizaemon XV is also known as Raku Jikinyu and was born in 1949. Interestingly, most sources refer to Kichizaemon XV as the current head of the Raku family. However, a brief reference on the Raku-Yaki website states that Kichizaemon XVI succeeded as the 16th generation Kichizaemon in 2019.

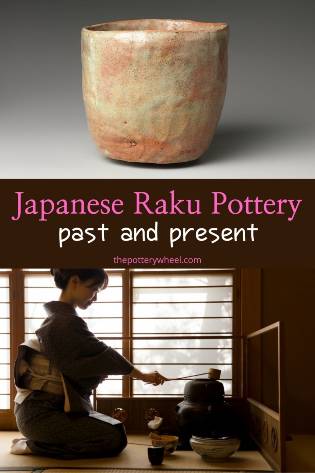

Japanese Raku Pottery

Raku Jinkyu has stated that he doesn’t like to be referred to as a potter. Nor does he like the label ‘artist’, which he feels is a musty old term.

Instead, he describes himself as a “maker of tea bowls”, or a “chawan’ya”. The word ‘chawan’ is Japanese for tea bowl. He feels that the term “chawan’ya” has a freshness that is more connected to the origins of Japanese raku pottery.

Wanting to be described as a maker of tea bowls highlights a couple of things about raku ware. Firstly, it points to the fact that Japanese raku is exclusively about the making of tea bowls.

Whilst western raku practices are used to make all sorts of different types of pottery and ceramics. The Japanese raku method is about making tea bowls.

The second thing that ‘maker of tea bowls’ points to, is a simplicity, which is central to raku ware.

Tea-Bowls

Tea bowls or ‘chawan’ are the drinking vessels that are used in the traditional Japanese tea ceremony. The tea ceremony dates back to the 1300s and different styles of tea bowls have been used over the centuries.

The Muromachi period took place between 1336–1573. During that time, the drinking vessels used in Japanese tea ceremonies were Chinese ware. These tea bowls had intricate designs, brilliant colors and were perfectly proportioned.

However, in 1573 the Muromachi government was overthrown. At this point in history, elaborate Chinese tea bowls were replaced in the tea ceremony by simpler Korean tea bowls.

Around this time there was a movement in Japan towards a way of life referred to as wabi-sabi. This is an outlook on life that recognizes the imperfection and impermanence of everything in nature.

During this time the elaborate excess of the Muromachi period was rejected. And there was a move towards simpler practices and tastes.

The emergence of Japanese raku pottery was a part of that movement.

Raku-Ware

The beginning of the Raku family and the development of raku ware is fascinating.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was a samurai and feudal lord in Kyoto. Some sources describe Hideyoshi as a warlord.

In 1574 a potter and tile maker called Chojiro was asked to make some tiles for Hideyoshi’s palace. Later, out of appreciation, Hideyoshi gave Chojiro a gold seal that had an inscription on it.

The engraving was of the Japanese symbol for Raku, which is means ease, comfort, happiness, pleasure, and contentment. From that time, Raku became part of the Chojiro family name.

Chojiro was the son of a Korean immigrant called Ameya, who settled in Kyoto around 1525. Ameya was a potter, who is thought to have made ware similar to what we think of today as Japanese raku.

Ameya and his wife Teirin both made tea bowls (source). Interestingly Teirin is the only reference to a female craftsperson that I came across in a long line of male raku potters.

In the 16th century, the wabi movement also had an influence on the tea ceremony. The ceremony was stripped back to its simplest form. This was known as wabi-cha, cha being Japanese for tea.

A well-known tea master, called Sen no Rikyu wanted to perfect wabi-cha. He sought out Chojiro to make tea bowls that embodied wabi principles.

The resulting simplified tea bowls created by Chojiro were the start of the raku tea bowl tradition.

What are Raku Tea Bowls Like?

Tea bowls are designed to sit comfortably in your cupped palms as you drink. They are round, with straight sides, and they rest on a narrow foot ring.

The word ‘simple’ is often used to describe the appearance of the tea bowl. However, Kichizaemon XV states that “simplicity” in the western sense, is not quite accurate.

When he describes the character of a tea bowl, he talks about restraint, stillness, and subtle irregularities.

Tea bowls are handmade rather than being made on a potter’s wheel. So, they are not perfectly round and they do have slight irregularities and deformities in their shape.

However, Kichizaemon is keen to point out that these deformities are not intentional. They aren’t ‘crooked, or wildly creative’. The slight distortions come from the process of hand-building and are not intended to be an expression of the artist’s self.

The tea bowl, with its subtle imperfections, is a universe of its own in the palm of the user’s hands. Kichizaemon states that “people feel comfortable opening their hearts to something that’s imperfect”. And by connecting to the imperfect tea bowl, we are connecting with nature.

Forming the Tea Bowl

Tea bowls are hand-built out of slightly sandy clay that is found at Fushimi on the outskirts of Kyoto. This clay has been stored by the raku family for many decades.

The hand-building process used to make a tea bowl is called the tezukune technique. This involves patting out a thick round circular slab of clay. The slab is then placed onto a simple banding wheel.

Next, the walls of the tea bowl are made by encouraging the edge of the clay upwards. This is done with the palm of the hands upon the outside wall of the bowl and thumb on the inside. The clay is turned as the potter gently pinches the bowl into shape.

Gradually the tea bowl is shaped using a mixture of squeezing the clay between the thumbs, fingers, and palms. The bowl is also patted with the fingers to coax it into its final shape.

Once the basic shape is formed, the bowl is left in a drying room for a few days to firm up. When it is leather hard, the shape of the clay is refined using a knife.

Traditionally they were carved using an iron or bamboo scraper. The walls of the tea bowl are carved away to make them thinner. And the foot ring is carved out of the firm clay too.

The carving process is intimate. The tea bowl is brought to the lips as it would be when it’s being used. This gives the maker a sense of what the tea bowl is like to hold and drink from.

Depending on how the bowl feels to hold and use, it will be carved some more. This process continues until the maker is happy with the shape and feel.

Firing the Tea Bowl

Once the tea bowl has been formed it is ready to be fired. Branfman (1991) points out that some sources assume that traditional Japanese raku pottery is not bisque fired. However, he states that this is incorrect, and that research indicates that raku ware is bisque fired before being glazed.

Japanese raku tea bowls are either black or red. Kichizaemon XV explains that the Chojiro experimented with different colors. And that as he sought to perfect the tea bowl, all colors other than black and red were discounted.

Red Raku Tea Bowls

Red Raku tea bowls are made from red earthenware clay. These earthenware bowls are fired at a lower temperature of around 900-1200F (500-650C). The iron and other minerals in the clay give the tea bowl its warm orange-red color. They are glazed with clear glaze.

It’s sometimes suggested that red tea bowls get their red coloring from an ochre slip that is applied before glazing. One example of this is Paul Soldner, a ceramic artist famous for American style Raku. Soldner states that ‘the color of red raku is obtained from an ochre slip’.

However, in an interview, Kichizaemon XV clarifies that red raku tea bowls don’t get their color from glazes or paints. Rather the color comes from the clay. The heat of the kiln oxidizes the clay’s iron, naturally turning it red.

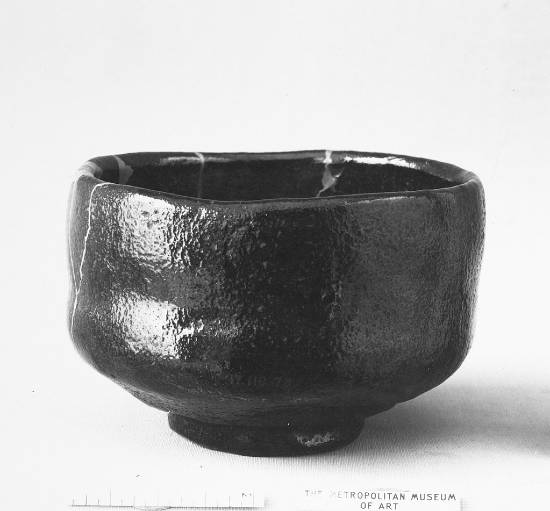

Black Raku Tea Bowls

By contrast, black Raku tea bowls are fired at higher temperatures, closer to stoneware temperatures. The temperature of the raku kiln when making a black tea bowl is between 2228-2291F (1220-1255C).

Black Raku tea bowls are glazed with a hand-crafted glaze made from pulverized stone. Over centuries, the raku family collected pebbles from Kyoto’s Kamo River.

The family keeps a collection of these stones, and when they make glaze, they carefully choose a selection of the stones. The stones are then crushed and ground to a fine powder. This powder is mixed with water to form a liquid glaze.

Around 10 layers of glaze are applied to the bowl before it is fired.

The Raku Firing Process

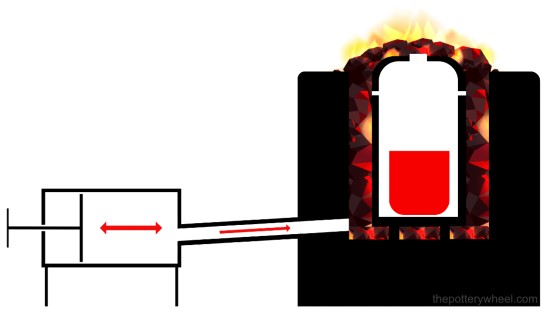

Red Raku tea bowls are fired in small batches of 4 at a time. By contrast, black tea bowls are fired individually, one at a time. Whilst raku is often described as a quick-firing process, firing a black raku tea bowl can take around 18 hours.

When firing a black tea bowl, the glazed bowl is placed in a saggar. The saggar is a container that protects the bowl from being in direct contact with the flames of the kiln.

The lid of the saggar has a hole on the top which functions as a spy hole. Potters are able to view the glaze on the tea bowl as it fires and gauge whether the glaze has melted enough.

Given by Kichizaemon XV to the V&A. Image by ThePotteryWheel

The saggar is placed in the kilns which and covered with binchotan charcoal. This is high-grade charcoal that is made from Japanese holm oak.

The benefit of using binchotan charcoal is that it burns slowly. Also, it has a high calorific content, which means it gives off more heat than regular charcoal.

Japanese raku firing begins around midnight, and normally 10 people are involved in the firing process. So, a lot of time and work goes into the production of one bowl.

The charcoal is set alight and the kiln is closely monitored to check the temperature of the kiln. The kiln is designed so that bellows can direct air into the hot coals and boost the kiln temperature.

The sound of the bellows, the look of the glaze, and the appearance of the flames are all monitored. These are used to gauge how long to fire the pot.

Removing the Tea Bowl From the Kiln

Once it is thought that the pot has been fired long enough, the pile of coals is knocked aside. The lid of the saggar is removed, and the pot is lifted out of the saggar using long iron tongs.

At this point, the tea bowl will be red hot. It’s a spectacular sight to see the glowing tea bowl lifted out of the hot kiln. This is one of the main differences between traditional Western firing and Japanese raku firing.

In conventional pottery firing, the pot is fired, and the kiln is allowed to cool before the pottery is removed. Allowing the kiln and pottery to cool is intended to protect the pottery from thermal shock. Thermal shock occurs when ceramics cool and shrink very rapidly, which can cause hot ceramics to crack.

By contrast, the raku process involves deliberately removing the clay at its hottest temperature. For this reason, the clay has to be selected carefully so that it can withstand the sudden temperature change.

Once removed from the kiln, the tea bowl is then allowed to cool naturally in the air.

It’s thought that the process of removing ceramics from the kiln when it’s hot was originally started to save time. Japanese tile makers were pushed to produce large quantities of ware. And it’s said that they tried this technique as an experiment to meet production deadlines. To their surprise, the tiles survived the process, and the practice continued as a method of production.

Different Styles of Japanese Raku Pottery

The process of making Japanese raku pottery has stayed the same for around 500 years. Each generation of the raku family has followed the tradition of their forefathers. In spite of this, the raku ware crafted by different tea bowl makers each have a distinctive look. Compare the following examples of tea bowls produced over the generations:

Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

© Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

Part of the reason for this variation in appearance is that there is no set recipe for the glazes used. Kichizaemon also states that the glazes used are not passed down through each generation. Instead, the next generation down has to figure out how to make the black glaze for themselves (source)

This allows for individuality and subtle differences in the glaze finishes and black tones found on different tea bowls. Over a tea bowl maker’s lifetime, the color of the glaze will change and evolve. As well as these apparent differences, each generation has its own personal seal, which distinguishes its work.

In spite of these differences, in Raku ware, the personality and the self-expression of the maker are not important. Instead, there is an emphasis on the individuality of the tea bowl itself. Each tea bowl is unique and given its own name.

Differences Between Japanese and Western Raku

Japanese raku pottery refers to tea bowls made by members of the Raku family heritage. They use a particular technique for forming the clay, and specific ways of glazing and firing their ware.

Western raku, often called American style raku is different. The western raku process involves techniques called post-firing reduction and fuming.

As with Japanese raku, the pots are removed from the kiln when hot. However, they are then often put into an enclosed container with a combustible material like straw, leaves, or paper. The closed (usually metal) container, combined with the burning material creates a reduction atmosphere.

In a reduction atmosphere oxygen is being burned out of the air in the container. The flames then search for oxygen in the pottery and glaze. This creates a particular organic-rich appearance in the glaze. And the unglazed parts of the pottery become carbonized and blackened.

Another difference is that the western technique is used to fire lots of different types of pottery. This might include amongst other things, bowls, ornaments, platters, or sculptures.

Western Raku

Members of the Raku lineage and Japanese art critics often don’t recognize these western practices as being raku techniques. There are several accounts of raku family members being baffled that the western approach is called raku.

Branfman relays one such account in his book ‘Raku: A Practical Approach’. He describes a discussion that took place between the American raku artist Paul Soldner and Kakunyu XIV, the 14th generation Kichizaemon.

This conversation was part of a discussion panel that was held at the World Crafts Council Conference in 1978. During the discussion, Kakunyu was apparently impressed by the American techniques of post-firing reduction and fuming. However, he was confused by it being called raku. (1991, p.7).

The Japanese Art Historian Tadanari Mitsouka attended the same event. He made a flat refusal to accept the western approach as being raku at all.

Paul Soldner himself reports that Kakunyu XIV described the western definition of raku as ‘interesting, but meaningless’. (source)

How did Western Raku Come About?

One of the first westerners to study raku and teach it outside Japan was the British potter Bernard Leach. Leach lived in Japan between 1909 and 1920.

At the time Leach was a painter but became inspired by Japanese ceramic practices. On his return to England, he set up St Ives Pottery in Cornwall. Where, amongst other techniques, he taught raku.

The use of post-firing reduction and fuming was introduced by Paul Soldner. On reading about Japanese raku, Soldner tried the technique.

However, he wasn’t pleased with the results he achieved. So, he experimented by putting the hot pot into a pile of pepper tree leaves. He liked the results and began to experiment more with this technique. This approach has evolved and been adapted by other potters since then.

Soldner, with some humility, acknowledges that calling this approach raku was “probably a mistake”. He recognizes that the confusion arose in the 1960s when not much was known about Japanese raku in the West.

Final thoughts

Japanese raku pottery refers to an ancient tradition. It refers to the making of tea bowls using particular techniques of forming and firing the clay. This tradition has been practiced and preserved by successive generations of the Raku Family for over 500 years.

The adoption of the word raku to refer to Western techniques does feel uncomfortable. When I started to learn about raku, I learned about western practices. It is only with hindsight that I’ve begun learning about Japanese raku pottery. It does seem as if the term has been if not hijacked by the West, then co-opted. Nevertheless, it’s good to understand the differences and appreciate the beauty of Japanese raku ware.