Majolica pottery means different things to different people. In this guide, we look at some of the different uses of the name Majolica, its history, who made it, and how it was made.

What is Majolica Pottery?

The name ‘majolica’ is used to refer to two different types of pottery that are made in different ways.

One use of the word majolica is to refer to tin-glazed earthenware that began to be made hundreds of years ago in various parts of the world.

The other use of the term majolica is to refer to colorful lead glazed earthenware that began to be produced around 1849 in Britain. During the second half of the 19th century, the production of lead glazed majolica spread across Europe and America.

One way to understand why the term majolica has been applied to different types of pottery is to look at the history of its production.

The History of Majolica Pottery

The process of making pottery usually involves firing the pots twice. The first firing is called the bisque or biscuit fire, and this turns the clay into undecorated ceramic pots.

These bisque fired pots are then covered with glaze. The glaze is applied as a liquid that dries to form a powdery layer.

When the glazed pots are fired a second time, the glaze melts and then turns into a solid glass layer as the kiln cools.

What is Tin Glazed Majolica?

‘Tin-glaze’ is glaze that contains tin oxide. The tin oxide gives the glaze an opaque white appearance when it’s been fired. Tin glaze is an ancient form of glazing and it was originally used to cover colored earthenware clay with a white surface.

The tin-glazing process usually involved bisque firing the pots and then applying a coat of tin glaze. Oxides were then used to paint decoration onto the unfired glaze. This was then fired a second time to produce decorated earthenware pots.

The Origins of Tin Glazed Majolica

Tin glazing had been going on for centuries and the production of tin glazed pottery in Spain plays a central role in the development of majolica.

It’s thought that tin glazing was already an established process in Spain back in the 8th century (Source, Hamer and Hamer).

However, in 711AD Spain was conquered by The Moors. The Moors were from North Africa and Damascus. They brought with them their own traditions around the decoration of ceramics, including the use of metal lusters.

The introduction of metal lusters altered the way that Spanish ceramics were decorated and began the Spanish tradition of producing lusterware.

Large Lusterware plate from Seville, Spain. Dated 1525-50

On display at the V&A Museum

Over the next few centuries, tin-glazed earthenware continued to develop in Spain and was exported to other countries.

By the 14th century, the lusterware of Spain was being exported to Italy. Much of this export took place via the Spanish island of Majorca.

It has been suggested that the name ‘Majolica’ actually arose because of the role that Majorca played in its export from Spain.

However, this idea is now thought to be incorrect. Another suggestion is that the name Majolica actually derives from the Spanish phrase ‘obra de Mallegua’ (source). This translates to ‘Malaga ware’, as in ceramics produced in the Spanish city of Malaga.

Italian Maiolica

Either way, the Italians embraced Spanish majolica, and in the 15th century began to produce their own. In Italy, majolica was called maiolica, because the letter ‘j’ wasn’t in the Italian language (source).

Initially the term ‘maiolica’ was used to refer to lusterware. But gradually, it came to be used to refer to all tin-glazed earthenware produced in Italy. Interestingly, when Italian maiolica was exported, it was referred to as faience, because much of it was made in Faenza, Italy.

workshop of Francesco Grue, Dated, 1640-50.

On display at The V&A Museum

The Rise and Fall of Tin-Glazed Ceramics

Over the centuries, the use of tin-glazing spread across Europe. In the 16th century, Italian potters settled in the Netherlands and introduced their techniques to the potters of Delft.

The Italian maiolica techniques helped the Delft potters to create convincing copies of Chinese porcelain out of earthenware clay. In the Netherlands, tin glazed maiolica became known as Delftware.

In Britain, English Delftware emerged as the maiolica techniques were adopted. Whilst in France maiolica became known as Faience, and in Germany Fayence.

Plate with Venus and Paris, Nevers, France, about 1641.

On display at The V&A Museum

The beauty of tin-glazing was that it allowed potters to cover up the underlying earthenware clay that was usually red, yellow, or buff. Tin-glazing gave the pottery a white surface that was perfect for decorating and allowed potteries to produce something that looked like porcelain.

This was at a time when the European potteries had not yet figured out how the Chinese had managed to make pure white porcelain clay.

However, in 1709, Johann Friedrich Bottger a German alchemist worked out how to make porcelain. And in 1710, a German pottery factory near Dresden started to make porcelain ware.

This was one of the factors that contributed to the start of the decline of tin-glazed earthenware. Once they could produce porcelain, the demand for tin-glazed ware began to fall away.

A Shift from Tin-Glazed to Lead-Glazed Majolica

Initially, tin-glazed earthenware made in Britain between the 16th and 18th centuries was called ‘galleyware’, or ‘galliware’.

The reason for this is that maiolica exported from Italy was transported by ship or ‘galley’.

However, in the 18th Century, under the influence of Dutch Delftware, tin-glaze earthenware made in Britain became known as English Delftware.

On display at The V&A Museum

For centuries, the term ‘majolica’ had been used in Britain as an anglicized version of the word maiolica. So, the word majolica had been in circulation for some time. However, in the 19th century, a different kind of pottery was produced that came to be called majolica too.

The Influence of Minton Ceramics

Herbert Minton was a ceramics manufacturer. In 1849, he hired a French ceramic artist called Leon Arnoux. Arnoux developed a series of colored lead-glazes.

Lead was added to the glaze mix to act as a flux. Fluxes work by lowering the temperature at which the other glaze ingredients melt during firing.

As a process, lead glazing had been around for centuries (source). However, these lead-glazes were special because the colors were vibrant, and had a soft high gloss. They also gave the ceramics a tough durable surface that was good for functional ware.

Together Minton and Arnoux worked on producing a new kind of ware. They designed a range of ceramic pieces. These were made using a range of techniques.

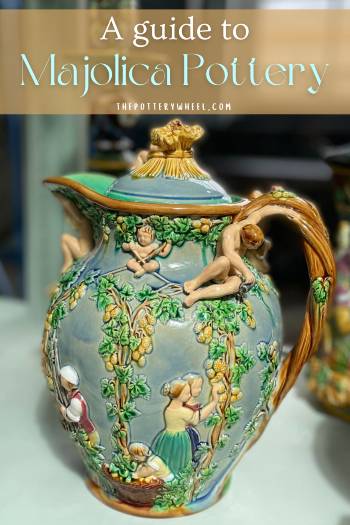

Some were made on the potter’s wheel, and then additional details that had been carved in clay were added to the wheel thrown base. And some pieces were hand built. Either way, the pieces had relief designs that gave the pots character and texture.

‘The Hop Jug’, about 1858.

On display at The V&A Museum

Once the original piece had been made, a plaster mold was taken and multiple copies of the original could be using the mold. Usually, strips of clay were pressed into a plaster mold to take on the shape of the original. The clay would then firm up in the press mold and could be removed once leather hard.

The mold for each piece was normally made out of a few sections. Once the clay was firm enough to be removed from the mold, the different pieces of clay would be joined together and dried out before they were fired.

The molded pieces were bisque fired, and decorated. The decorating process involved painting the bisque ware with a number of colored lead-glazes. Once glazed the pieces were fired one more time.

The Arrival of Victorian Majolica

Minton and his team had been working on his colorful lead glazed ceramics for a couple of years. And in 1851, he exhibited some of these products at the first Great Exhibition. The exhibition was intended to be a celebration of art in industry (source).

At the time, Minton referred to these pieces as Palissy Ware. The name Palissy ware is a reference to Bernard Palissy who was a 16th-century French potter.

Palissy Ware

Bernard Palissy was known for making highly decorated pieces. His work would often include lizards, insects, and other animals. He called these pieces ‘rusticware’, and would sometimes use casts of actual insects and animals to decorate his work.

Palissy’s very naturalistic style was the inspiration behind what became known as Palissy ware.

Dish, probably Paris region, follower of Bernard Palissy 1580-1620.

On display at The V&A Museum

It is because of the painted relief details on Minton’s newly launched product that he referred to it as Palissy ware. However, Minton also began referring to his lead-glazed pottery as majolica. As a result, his Palissy ware soon became known as majolica ware.

The process of making this kind of majolica was very different from the earlier tin-glaze majolica that originated in Spain. These days, Minton majolica and the majolica it inspired is called ‘lead-glaze majolica’. Victorian majolica refers to majolica made between 1849 and 1900 (source).

Rather confusingly the term ‘Victorian majolica’ refers to tin-glaze majolica made at that time, and also lead-glaze majolica.

However, after 1851 lead-glaze majolica enjoyed a huge surge in popularity and overtook the production of tin-glazing. Other pottery companies in Britain began to produce their own lead glaze majolica ware. The other two main British producers were Wedgewood and George Jones.

In addition to this, the techniques and methods of producing lead-glazed majolica spread across Europe. This is now referred to as Continental Majolica. And in 1870 lead-glazed majolica started to be produced in America.

Different Types of Majolica Pottery

Here are some of the main types of majolica, categorized broadly according to where they were made.

English Majolica Pottery

Before the introduction of lead-glazed majolica, English pottery factories produced tin-glazed majolica. A lot of this was made in the style of Italian Renaissance maiolica.

Early Spanish majolica had a free, relaxed, liberal Mediterranean look and feel. By contrast, a lot of Italian Renaissance maiolica was precise, highly detailed, and often used to represent ideas or stories.

Davidmadelena, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons,

Image is cropped.

When lead-glazed majolica was introduced in 1851, it became very popular. Majolica was brightly colored and often beautifully designed. This made it very appealing to the Victorian middle classes, who wanted to decorate their homes.

What is more, because it was made from molds, it could be mass-produced easily. This made cost-effective for manufacturers to make. And it was more affordable for many households.

‘Game Dish’, about 1860.

On display at The V&A Museum

Although relief molds made the manufacture of majolica less expensive, other items were intricate inlaid pieces that were made to emulate rare Renaissance artifacts.

On display at The V&A Museum

In the two decades after the exhibition in 1851, the production of lead glazed majolica took over tin-glazed ware. Many other potteries besides Minton started to make their own lines of ware.

Wedgwood Majolica

The first big manufacturer after Minton was Wedgwood. Wedgwood was founded in 1759 and they started to produce majolica around 1860. They produced lead-glazed majolica for around 30 years.

Daderot, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Wedgwood produced a lot of ‘Green Majolica’. This was a particular style of majolica that was, decorated with molded leaf patterns.

The green lead glaze pooled in the textures on the surface of the pottery. This would highlight the leaf patterns on the design. This effect is called ‘intaglio’. You can see this effect on the leaves of the ‘cauliflower coffee pot’ pictured above.

Another feature of Wedgwood Majolica was the use of tortoiseshell glazing. This was a technique that was often used on the underside of majolica ware. Glazes were used to create a mottled effect in brown, yellow, green, or sometimes blue.

However, tortoiseshell glazing wasn’t just used on the underside of majolica. It was also used to glaze the top side of some pieces.

Image courtesy of Lovable Antiques

George Jones Majolica

George Jones was an apprentice at the Minton factory from the 1830s. After years of working independently, in 1866 he built what was originally called The Trent Potteries. It became known later as the Crescent Potteries.

It was in the Trent Potteries that the George Jones company began to make majolica. And by 1870, they were known for producing majolica that was elegant in design and beautifully made.

Image courtesy of Oriole Antiques

George Jones ceased trading in the 1950s. Sadly by 2001 each of the three buildings that made up the Trent Potteries had been demolished (source).

Image courtesy of Oriole Antiques

English Majolica At Its Peak

Lead glazed majolica took the ceramic world by storm after its introduction in 1851. It was popular in Victorian households. Objects ranging from garden seats, large platers or jardinieres, big decorative pedestals to dinnerware were made from majolica.

On display at The V&A Museum

Its popularity was reflected in buildings such as the V&A museum. Majolica ware formed a large proportion of the original objects showcased at the V&A when it was first built. But also, a lot of the V&A building was decorated using majolica installations.

These days, Victorian majolica is only a small section of the museum’s huge collection. However, there is evidence around the museum of how important it was in its heyday.

Continental Majolica Pottery

Potteries also sprang up throughout Europe producing lead glazed earthenware. The spread of ceramic skills and techniques was partly due to the movement of potters between countries.

This exchange of skills was a two-way street. Many French potters such as Leon Arnoux moved to Britain and brought their expertise to them.

Here is another example of the French influence on English Majolica

Manufactured Minton, England. 1868.

Public domain. Image courtesy of The Met Museum.

But, equally, Staffordshire potters moved to the continent and took their skills and knowledge elsewhere.

French Majolica

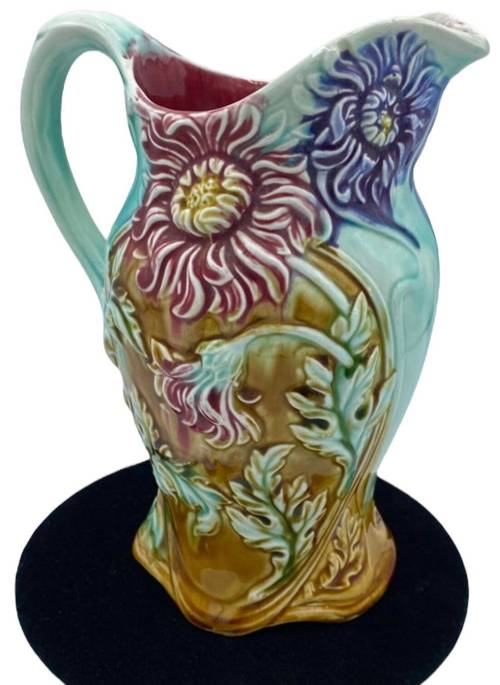

French majolica is also often called Barbotine. Barbotine is a broader term that refers to pottery that has been given textured relief decoration using clay slip. The clay slip is piped onto the surface a bit like the icing on a cake.

However, the word barbotine is also used in a more specific way in France to refer to majolica.

Image courtesy of Kimms Attic

Belgium Majolica

The Mouzin-Lecat majolica factory of Wasmuel, in Belgium was established in 1878 on the French north border.

Image courtesy of Kimms Attic

Austrian Majolica

Image courtesy of Meryk Antiques

German Majolica

Image courtesy of Vintage Artperience

American Majolica Pottery

Production and interest in majolica was beginning to fall off in the UK around 1870. However, its popularity was beginning to gain traction in the US around this time.

Lead glaze majolica had been produced in the US since around the 1850s. Many potters from the UK, notably from Staffordshire migrated to the US and took their skills and knowledge of majolica with them.

This migration played a role in the evolution of majolica in the US. A good example of this is the company of Griffin, Smith, and Hill, who are the most well-known producers of American Majolica.

John Smith was an English potter from Stoke on Trent. He went into partnership with William Hill and Henry and George Griffen in 1871. In 1879, Griffin, Smith, and Hill launched a popular range of majolica called Shell and Seaweed, and American majolica took off in a big way.

Etruscan Shell and Seaweed Majolica Bowl.

Image courtesy of AyCarambaGifts

As well as featuring aquatic themes such as seaweed, shells, and dolphins, Griffin, Smith, and Hill also produced majolica with agricultural themes. These pieces featured fruit and vegetables such as cauliflowers, corn, grapes, and strawberries (source).

Image courtesy of Kereks Boutique

Griffin, Smith, and Hill called their pottery Etruscan works, so their majolica is also known as Etruscan majolica.

Other American Majolica Pottery Companies

- Morley & Co. Ohio

- Eureka Pottery co, New Jersey

- Joseph Mayer’s Arsenal Pottery, New Jersey

- F D Haynes & Co, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore

- Peekskill Pottery Works, New York

- James Cares New York City Pottery

- Edwin Bennett Pottery Company, Maryland

Public domain. Image courtesy of The Met Museum

The Decline of Majolica

In England, majolica production was at its highest at around 1870. This was just 20 years after it had been introduced. However, after its peak, its popularity had begun to wane and by 1880, majolica sales in Britain had fallen significantly.

This may be partly to do with the economic recession at the time which affected consumer demand. But there may be other factors involved, such as a change in public tastes.

In 1860 the Arts and Crafts movement started in Britain. And this brought with it an appetite for a style of pottery that was different from Victorian majolica.

The British love affair with majolica was intense but relatively brief. To put this into perspective, George Jones only produced majolica for 20 years. They had been later to start making majolica than Minton and Wedgewood, and by 1886 their majolica manufacture had been discontinued.

In America, majolica continued to enjoy popularity until around 1920. Its worldwide popularity was reflected in an exhibition in 2022 at The Walters Art Museum called Majolica Mania, which featured 350 pieces of majolica.

Different Styles of Majolica Pottery

Majolica was also produced in a range of different styles, reflecting the various influences of the day. Here are some of the popular styles found in majolica ware.

- Gothic influences

- Naturalism

- Evolutionary ideas

- Style resonant of the French Empire

- Oriental influences

- Egyptian styling

Majolica and Lead-Glazing

Because of a growing awareness of the health hazards posed by lead, since the 1970’s the ceramics industry has moved away from producing lead-glazed pottery (source).

So, even if lead glazed majolica had not fallen out of fashion around 1920, it’s production would have been curtailed by concerns around lead-glazing.

That being said, Wedgewood re-ran some of its most popular lines of majolica using lead-free glazes.

Final Thoughts

Although lead glaze majolica production ran its course around a century ago, it still inspires passionate interest in collectors. Majolica pottery is still an enduring feature of important cultural landmarks such as the V&A museum. And the Majolica International Society has an active membership and is an incredible resource for anyone wanting to know about majolica ware.

Leave a Reply