Your cart is currently empty!

Crazing in Pottery Glaze – Causes & Ways to Prevent It

Published:

Last Updated:

Affiliate Disclaimer

As an affiliate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases. We get commissions for purchases made through links on this website from Amazon and other third parties.

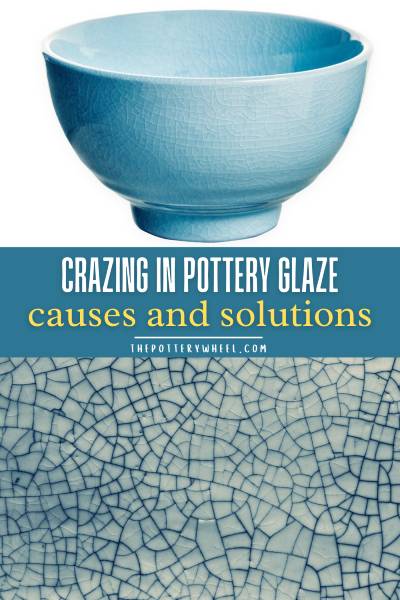

Crazing in pottery glaze is a network of very fine cracks that cover the glaze on a piece of ceramics. Sometimes potters deliberately want to create a crazing effect, and this is known as crackle glaze. But a lot of the time crazing is considered to be an unwanted glaze defect.

Crazing happens when a glaze is too tight for a piece of pottery. Clay and glaze expand and contract as the kiln heats and then cools. This is thermal expansion. If the glaze has a higher rate of thermal expansion, it contracts more than the clay as the kiln cools. This puts the glaze under stress, and it will craze to reduce the tension.

The good news is that crazing can be prevented by using clay and glaze that expand and contract by the same amount.

How to Spot Crazing in Pottery Glaze

Sometimes crazing in pottery glaze is obvious. This is especially true of older ceramics where the cracks in the glaze have darkened over time. But it can be harder to spot on newly made pottery.

If you’re a potter, you probably know that heart-sink moment when you take a piece of pottery out of the kiln and hold it up to the light. It all looks great until you look a little closer and spot a fine network of tiny cracks that have spread across the glaze.

Sometimes these cracks are so fine that you have to squint to see them. But once your eyes have focussed on them, it’s hard to see anything else.

When Does Crazing Happen?

Sometimes crazing in pottery glaze happens immediately as the kiln cools down. If the crazing happens straight away, you might even hear it going on in the kiln before you’ve opened the lid.

When pottery glaze crazes, it makes that ‘ping, ping, ping’ noise that you might have heard coming from freshly fired ware. The pinging noise might sound innocent enough, but if you hear it, you know that there is a problem with the glaze.

So, occasionally you might notice that a network of cracks has formed even before the pottery has been taken out of the kiln.

Other times, the crazing might start once the kiln has been unloaded. If it happens shortly after unloading, you might actually get to see how the crazing pattern forms.

Usually, the first crack is a long crack that goes right across the pottery glaze. The crack will spiral up the length of a pot from the base to the top. Alternatively, if it’s a large flatter piece like a plate, the crack will cover the diameter of the plate.

This is called ‘primary crazing’ (source, Hamer and Hamer). If you were to look at this first crack under a microscope it would be quite wide.

However, the glaze is still under a lot of tension, and secondary cracks then form around the first main crack. These smaller cracks form a network of triangles and squares and usually cover the whole surface until enough of the tension in the glaze has been removed.

As the smaller cracks form, the first long crack will close up as the stress is released.

Delayed Crazing

Crazing in pottery glaze doesn’t always happen immediately. It can start to show up weeks, months, or even years after the pottery has been made.

This is particularly true of earthenware pottery. The reason for this is that earthenware pottery is porous, and even when it has been glazed, it will absorb moisture from the environment.

As moisture is absorbed into the underlying ceramic body, the ware will expand a tiny amount. But this tiny expansion is enough to increase the stress that the glaze is under and cause it to craze.

But it’s not just earthenware pottery that will craze later on. Stoneware and porcelain can also have delayed crazing. It may be that the glaze has always been under tension, but just managing to hold it together.

However, over time, changes in temperature from day-to-day use, or knocks and bumps from being handled will prove too much for the glaze to manage. As a result, crazing can form in the glaze at a later point in the pottery’s life cycle.

What Causes Crazing in Pottery Glaze?

As I mentioned earlier, crazing happens when the glaze is too small for the underlying clay body. When the pottery is fired, as the temperature in the kiln rises, the glaze melts to form a molten layer on the pottery.

In its molten state, the glaze covers the clay nicely. During firing the clay also becomes softer and elements within the clay melt as well. Ideally, the clay doesn’t become so soft that it warps or loses its shape. Nevertheless, the clay particles and glass formers in the clay move about too.

As the pottery heats up, the clay and glaze expand. The amount that they expand is called the coefficient of thermal expansion, or CTE for short. This sounds scientific and a bit off-putting, but basically ‘coefficient’ means the rate or amount that they expand and contract.

Each clay and glaze will have its own specific rate of thermal expansion. You can usually find the CTE of a clay body, and sometimes the glaze on a pottery supplier’s website.

Just look up the clay body you like to use and search for a section called something like ‘technical data’. The CTE will probably be listed there.

The rate of thermal expansion is normally written as a number and will be something like ‘6.9’. This number refers to very tiny changes in the size of the clay and glaze as they are being fired. For example, a CTE of 6.9 refers to a change of .00000069 inches per degree change of temperature.

Even though the shifts in size are tiny, they are enough to have a big impact on whether the clay and glaze work together.

Glaze Fit

To avoid crazing in pottery glaze, the rate at which they expand and contract needs to be compatible. If the glaze expands more than the clay when it heats up, it will also contract more than the clay as it cools down.

As a result, when the glaze cools down it’s stretched over the clay body, and it will be under a lot of tension. So, the glaze and clay need to contract at more or less the same amount.

That being said, ceramics manufacturers usually aim to use a clay body that shrinks just a little bit more than the glaze. The reason for this is that if the clay body shrinks just a little bit more the glaze will be compressed. This compression helps to prevent crazing from happening.

But it’s a balancing act. If the glaze is compressed too much, you can encounter a different glaze defect which is the opposite of crazing. This is called ‘shivering’ and it happens when the glaze is too large for the clay body.

This mismatch also puts the glaze under a lot of tension and can lead to shards of glaze popping off the surface of the pottery.

How to Prevent Crazing in Pottery Glaze

So, what does this all mean for you if you have unloaded your kiln and found that your pots have been blighted by a bad case of crazing? What can you do to prevent it from happening again?

The bad news is that if your pottery has already been fired and started to craze, there is nothing that you can do about it. The glaze is under tension, and it will continue to craze until the tension has been reduced.

However, you can use it as a learning experience and find a way to prevent it in the future.

Two Suggestions That I Haven’t Found Helpful

So, what can you do to prevent crazing? If you read around, you will find a few suggestions about tweaks you can make to how you glaze and fire to reduce the chances of crazing. However, I have to say, I haven’t found these easy fixes especially effective.

1) Program The Kiln to Cool Down Slowly

One suggestion sometimes made is to slow down the cooling segment of your firing schedule. The idea behind this is that you can ease the glaze into a fitting over the clay body.

I haven’t had success with this and the reason it doesn’t make much difference is that the glaze doesn’t fit regardless of how slowly you cool the kiln down.

It may prevent the glaze from being crazed when you unload the kiln, but the tension will still be there. And it won’t take much day-to-day usage before the crazing begins to show up.

2) Don’t Apply the Glaze Too Thick

I have found that if a glaze crazes, it does tend to craze more on those parts of the pot where the glaze is thicker. But, if I have a glaze that crazes on a clay body, I find that it will craze sooner or later regardless of how thinly I apply it.

Also, it doesn’t sit right with me to cover up a glaze defect by adapting the application. I’d rather use a glaze that fits the clay body well.

Helpful Ways to Prevent Crazing

If these tweaks don’t work for you either, what can you do to prevent crazing on pottery glaze? There are two approaches you can take.

- You can either swap your glaze or clay body and try to find a combination that works better together.

- Or you can make adjustments to the glaze or clay chemistry to get them to perform differently.

Of these two options, the first option of finding a clay body that works better with your glaze is the simplest. So, let’s take a look at that option now…

Finding a Combination of Clay and Glaze That Fit Each Other

Glazes have a specific look, and if you love the glaze, your easiest option is to try another clay body.

If you are using commercially made glazes, I’d suggest reaching out to the manufacturer and asking for some recommendations of clay bodies that work well with that glaze.

Or you could try putting out a message on a pottery forum to see what clay body other potters use with that particular glaze.

Alternatively, you can do some test tiles and try the glaze on a few different clay bodies. That way you can see which clay body works well with your glaze.

Also, double-check the firing range of the clay body. Are you glaze-firing your clay body in the right temperature range? Stoneware clay that is being glaze-fired at earthenware temperatures isn’t mature.

You are more likely to get crazing if you are using low-fire glazes on stoneware clay and firing it at earthenware temperatures.

Adjusting The Clay Body or Glaze

Crazing occurs because the glaze contracts more than the clay body when it’s cooling. So, if you are into chemistry and want to experiment, you can try to adjust your materials.

To prevent crazing, you can make additions to the clay body to make it contract more on cooling, i.e. to raise its thermal expansion. Or you can adjust the oxides in your glaze to reduce the rate of thermal expansion and therefore lower how much it contracts.

Adapting The Clay Body

Like a lot of potters, I buy my clay from a supplier. The prospect of adjusting its composition to change how it behaves in the kiln feels way beyond my ken.

Nevertheless, I can get a bit nerdy about chemistry and I’m interested in how this works.

One of the suggestions sometimes made to reduce crazing is to add more silica to your clay body.

This can work because of something called the ‘cristobalite squeeze’. When clay is fired to the point of vitrification, the silica in the clay forms something called cristobalite. This is a crystalline form of silica.

When cristobalite is heated, it expands by 3% in volume at the temperature of 226C (439F) (The Potter’s Dictionary, Hamer & Hamer). Likewise, when it cools down, it contracts by the same amount. If you add more silica to the clay, more cristobalite is formed. As a result, there is a sharp contraction in the size of the clay during cool down.

This contraction has the effect of compressing the glaze and can be a way of preventing crazing from occurring. But, it’s a balancing act, because too much silica can compress the glaze too much and lead to shivering. Or it can lead to ‘dunting’, which is when the clay body cracks.

Whilst this is fascinating, it’s easier to adjust glaze chemistry than it is to adjust a clay body.

Adapting the Glaze Recipe

If you have made a glaze according to a glaze recipe, or you have created your own glaze, you can adjust it to reduce the amount it contracts on cooling.

Some glaze ingredients such as potash and soda have a high rate of thermal expansion. Crazing can be reduced by decreasing the amount of potash and soda used in the glaze recipe.

Other glaze ingredients have a lower thermal expansion. You can reduce the amount that a glaze contracts on cooling by adding the following to your glaze:

- Silica

- Alumina

- Boron

Is Crazing in Pottery Glaze Bad?

All this testing and adjusting takes time and thought. Is it worth it? Is crazing in pottery glaze all that bad? The answer is yes, crazing in glaze is a problem for a couple of important reasons.

Reason 1) Pottery Strength

Crazing makes pottery considerably weaker and less functional. It’s easy to assume that crazing is just a surface issue. After all, the glaze seems like a thin layer that covers the outside of the clay body.

However, when they are fired, clay and glaze pass materials between one another. This blend of components creates a clay glaze interface.

If the glaze is fired at mid and high-fire temperatures, the glaze doesn’t just sit on the surface. Instead, it becomes bonded to the clay body and becomes part of the surface of the clay.

As a result, cracks in the glaze reach all the way down to the clay body and cause tiny cracks in the surface of the clay too. These tiny cracks become points of weakness in the pottery.

Research indicates that the strength of pottery with a crazed glaze is compromised. For example, B. Pinto’s research states that…

“cracks in glass (glaze) create ‘a fracture path which can become a large flaw within the material…These flaws can easily propagate through the material and cause failure under a relatively low external load’ (source).

Reason 2) Bacteria and Contamination

The cracks in a crazed pottery surface can harbor bacteria and mold, which is a source of concern from a hygiene perspective. You can read more about crazed pottery and food safety here.

How to Test Your Pottery for Crazing

If you want to make completely sure that your pottery glaze won’t craze, you need to stress test it.

There are different ways of doing this, but most of them involve subjecting test samples of the glazed pottery to different temperatures.

One approach is to put a glaze test tile in a pan of boiling water and leave it there for 10 seconds. Remove the test tile carefully with tongs, and put it into a pan of icy water. Let the tile rest there for another 10 seconds. Repeat this process a number of times to put the glaze through its paces.

Then remove the test tile from the water and dry it. You can inspect it visually to see if it has crazed.

You can also rub some Indian ink or a wipable marker pen onto the surface of the glaze and wipe the excess off with a damp cloth. If there is any crazing on the glaze surface the ink will make these fractures visible.

Visit The Pottery Wheel Store

Fancy treating yourself to some homemade pottery? Looking for a unique gift? Check out my handmade pottery store…

Final Thoughts

Crazing in pottery glaze is frustrating. It’s one of the reasons that I got into the habit of testing all glazes on the clay that I use before I commit to using it on a batch of pots. Testing glazes takes patience, but it’s worth it in the long run to avoid ruining your painstakingly crafted pottery.