Your cart is currently empty!

How is Rookwood Pottery Made? Art, Craft, and Science

Published:

Last Updated:

Affiliate Disclaimer

As an affiliate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases. We get commissions for purchases made through links on this website from Amazon and other third parties.

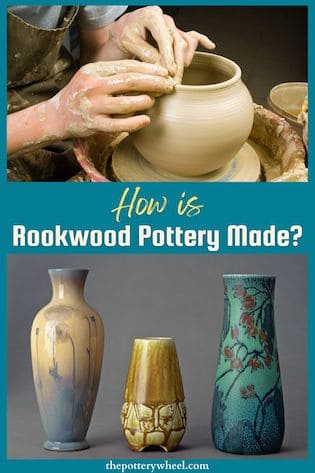

Rookwood Pottery is a celebrated part of the American Art Pottery movement. It was founded in 1880, and over the years the techniques used to make Rookwood have evolved. But how is Rookwood pottery made? And how have these techniques changed with time?

During its history, Rookwood Pottery has been owned and run by a number of different people. It has also been located in different parts of the US. Different eras have been marked by different production techniques. Though over the years, it has been made using both the potter’s wheel and with plaster molds.

To get some context, it’s helpful to start at the beginning and see how these methods have evolved. So, we start with how Rookwood Pottery was made in the early days of its production…

The Origins of Rookwood Pottery

Rookwood was the brainchild of potter and ceramics decorator Maria Longworth Nichols Storer. She opened the pottery in 1880 in a deserted schoolhouse on Eastern Avenue in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Maria had two significant driving ambitions. The first ambition was that she wanted American ceramics to achieve a higher acclaim in the eyes of the world than it had in the past. She was a great admirer of Japanese and European (especially French) ceramics.

Her vision was that Rookwood pottery would produce beautiful pottery that would rival her Japanese and European counterparts. As such, she was focused on producing highly crafted and exquisitely rendered bespoke pieces of pottery.

However, in addition to this, she also wanted to make beautiful pottery accessible to all. She called her ceramics ‘art pottery’ and wanted to bring beauty into people’s homes. Her dream was to elevate their lives and living spaces.

As a result, Rookwood began its journey with two broad goals in mind. The first was to create refined one-off pieces that would capture international attention. The second was to create lovely ceramics that the general public could own and enjoy.

How Was Rookwood Pottery Made in the Early Days?

These two goals were reflected in the two production processes that were used from the beginning at Rookwood.

Maria was a potter and an artist. But she was also a savvy businesswoman; from the beginning, she employed skilled local artists and potters.

Maria and her employees would make one-off pieces of pottery on the potter’s wheel. At the same time, Rookwood Pottery also made production pieces of pottery using plaster molds.

Let’s take a look at how Rookwood pottery was made using both of these techniques.

The Clay

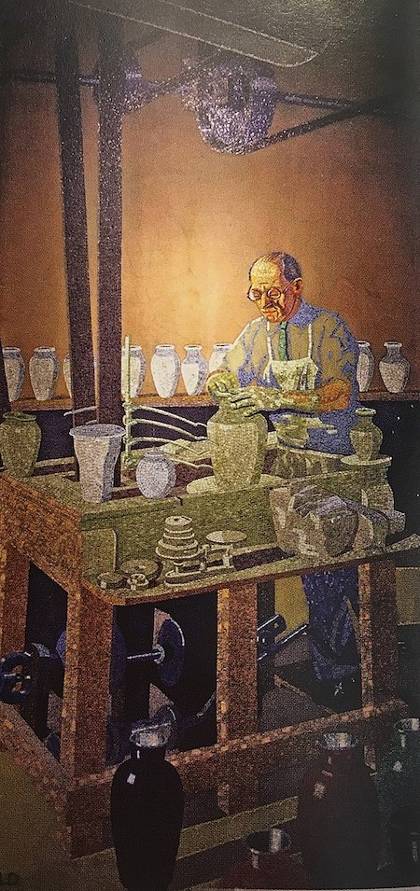

Even in the early days, the pottery had different teams that specialized in different areas of production. The very first stage in the production process was making up the clay body itself.

In the beginning, Rookwood used local Ohio clay. It arrived at the factory in a powdered form. It was then made up to the right consistency, depending on whether it was going to be used for plaster molds or on the potter’s wheel.

A worker would shovel powdered clay into a blender, which would mix the powder with water. The liquid clay was passed through a mesh to remove any lumps or contaminants from the mix.

If the clay was going to be wheel thrown, it was blended into a plastic consistency that could be worked by hand.

The Potter’s Wheel

Marias’ team of potters threw many bespoke pieces of pottery. These included a range of items from vases, pitchers, dinnerware, umbrella stands, ice tubs, wine coolers, and water buckets.

Once the piece had been thrown, it was taken to the decorators, who would paint the raw clay before it had been fired in the kiln.

The Decorating Process

The Rookwood artists used a number of decorating techniques. Two of the most important techniques involved decorating the pottery with colored clay slip. Slip is clay that has been mixed with enough water so that it has a liquid consistency.

Adding certain minerals to the liquid creates colored slip that can then be applied to the pottery as decoration.

The painters would either paint the colored slip onto the pots. Or they would use a technique sometimes called Barbotine, where thicker clay slip is applied to the pottery. This created a relief texture on the pots so that the designs stand out from the pottery surface.

The artist Laura Anne Fry, who worked as a decorator at Rookwood is said to have invented a mouth-blown atomizer. This allowed the artists to graduate colors on the pottery as one shade blended evenly into another.

The painters would sign the bottom of the piece with their initials.

Other decorating techniques involved painting designs with underglaze or carving patterns into the clay surface using a sharp carving tool. The carving technique is known as incising.

Image courtesy of jmwgallery.com

Plaster Molds

If the clay was to be used in a plaster mold, it would be mixed to a liquid pourable consistency. This was then poured into the mold and allowed to sit for a brief period of time.

This process is called slip casting. As the clay sits in the mold the plaster draws water out of the liquid clay. Because the water is being sucked out of the slip, a solid skin of clay forms on the inside surface of the mold.

The mold is then turned upside down, and the excess clay slip that is still liquid is allowed to drain out of the mold. A layer of stiff clay remains on the inside of the mold. This is allowed to firm up. Once the layer is firm, the mold is removed to reveal the cast piece of pottery. You can read more about slip casting here.

Rookwood Pottery designed and made these plaster molds. And over the years that they were in operation, they produced thousands of molds for different designs. Many of these molds were lost over the years. But thousands of the original molds still exist in the Rookwood archives today.

Once the pottery had been released from the mold, any seams or imperfections on the clay surface would be tidied up.

The Kilns

Kilns are large ovens that heat to a very high temperature and are large enough to bake pieces of pottery.

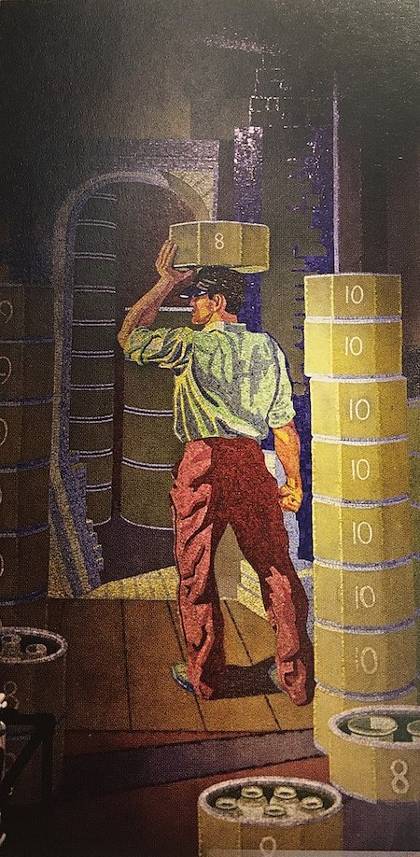

The kilns at the first Rookwood pottery were coal-fired. They were brick kilns that were large enough for more than one kiln worker to step inside.

Firing pottery with a coal-fired kiln is a messy business. The atmosphere in the hot kiln would have been full of fumes and smoke. To protect the finely decorated pottery from the dirt in the kiln, the pots were fired in saggars.

A saggar is a container made from refractory material that can survive the heat of the kiln. The saggars were cylindrical, and a few pieces of pottery would be placed in each saggar. To save space in the kiln, several saggars were stacked on one another.

Once the kiln was loaded the door of the kiln needed to be closed. But unlike kilns today where you can simply shut the lid, the coal-fired kiln door needed to be bricked up. Bricks were cemented into place to shut the kiln and it was then fired for 30 hours.

The Firing Process

Usually, the pottery was fired twice. The first firing is when the pottery is transformed from fragile, soluble clay into hard, non-soluble ceramic material. This is called the bisque fire. During the first firing, the kiln reached a temperature of around 1,200F (650C) (source).

This bisque firing temperature is cooler than the temperature that we generally use today. These days, it’s common for potters to bisque fire at temperatures around 1832F (1000C)

When the firing schedule had come to an end, the kiln would take another 4 days to cool down. The brick door would be removed and the kiln was unloaded.

The pots were then inspected, and if they were in good condition, they would be sent to be glazed.

The Glazing Process

In the early days of Rookwood Pottery, the pots were glazed by being dipped in a bucket of glaze. The glaze would be allowed to dry on the decorated pot surface. Then they were reloaded into the kiln for a second firing.

During the glaze fire, the glaze coating would melt and form a glassy protective layer over the decorated pots.

One of Maria’s talents was for hiring people who could help her to develop and finesse the Rookwood lines. From the off, she hired chemists who worked on developing distinctive pottery glazes.

Two of the notable early glaze chemists at Rookwood were Joseph Bailey and Karl Langenbeck. Also, Chicago pharmacist Dr. William S. Christopher worked as a consultant chemist for Rookwood conducting experimental research on glazes and clay bodies.

After a few years of testing and experimentation, the Rookwood glaze chemists developed 3 glaze lines. These included Cameo, which was later renamed ‘Ivory ware’, Dull Finish Glaze, and Standard Glaze.

Dull Finish Glaze

This was a matte finish, as illustrated in this jar by A. R. Valentien.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Standard Glaze

However, of the three lines, Standard Glaze became one of the looks that Rookwood has become most famous for.

In ‘The Rookwood Book’, first published by Rookwood Pottery in 1904, they describe their standard glaze as ‘noted for its low tones, usually yellow, red and brown in color’. It ranges from ‘light and golden’ in color, to ‘deep rich red, brown, and green combinations.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tiger Eye Glaze

Another acclaimed glaze produced by Rookwood was Tiger Eye, first produced in 1884. Legend has it that it was an accident, however, it was much admired, and Rookwood spent several years afterward trying to recreate the effect. Tiger eye was used on red clay and produced a golden shimmering effect.

Other Glaze Lines

Some of the other original glaze lines include the following:

- Iris Glaze

- Sea Green

- Ariel Blue

- Black Iris

- Vellum

- Black opal

Moving Into a New Era

In the first 10 years of being in production, Rookwood Pottery won a number of awards and achieved international recognition. Nevertheless, in 1890, Maria transferred ownership of the pottery to William Watts Taylor.

Taylor made a number of changes when he took over. One change was that he formalized the status of the pottery which became a company. Also, in 1892 the pottery moved to a new premised in Mount Adams, Cincinnati.

The premises were larger, so they could employ more staff. And it also had improved facilities, including oil-burning kilns.

Oil-burning kilns have a few advantages over coal kilns. They can achieve higher temperatures, they are more efficient, and they are a cleaner way of firing ware.

Interestingly, the kilns in the Mount Adams pottery were left in situ after the pottery moved elsewhere. The historic kilns became a feature in what became The Rookwood Restaurant.

How Was Rookwood Pottery Made at Mount Adams?

When Rookwood moved to its new location the pottery was still made using the same techniques of throwing and using molds. However, there were a few additions and changes to their production processes. Here are a few of the changes that occurred…

Architectural Ceramics

In the 1890s Rookwood started to experiment with making architectural ceramics to be used to decorate buildings. This included items such as tiles, plaques, and fire surrounds. Architectural ceramics are sometimes called ‘architectural faience’ and it is made from glazed terracotta clay.

The process that Rookwood used to make their tiles involved pressing clay into plaster molds. As with their pottery, Rookwood quickly made a name for themselves in architectural ceramics.

They won prestigious contracts to make tiles for high-profile installations such as some stations for the New York Subway. You can read more about this history here.

Electroplated Rookwood Pottery

Over the years Rookwood pottery has worked in many styles. This includes Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Impressionist, and also Japanese-style designs.

One striking strand of their work was a period of time in which they combined ceramics and metalwork. During this period their ceramic work was embellished with sterling silver overlay. Some of this work was done by a manufacturing company in Rhode Island called Gorham.

The pottery would be finished and glazed at Rookwood and then sent to Gorham for the additional silverwork to be added. The process that Gorham used was called electroplating.

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum,

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

However, not all Rookwood pottery that has metalwork was produced by Gorham. For example, various items such as lamps or vases were mounted on metal bases.

Some of these were made internally at Rookwood and others were made in Japan. This Japanese-made metalwork was imported back to Rookwood and added to the finished ceramic piece.

Also, in the 1890’s a Japanese metal worker called E.H.Asano came to work at Rookwood for a few years. He had been introduced to Rookwood by Kataro Shirayamadani, a Japanese painter who was one of Rookwoods’ most important pottery decorators.

After Asano left Rookwood, some of the artists continued to use metalwork in conjunction with their ceramic ware. Shirayamadani made some of the most well-known pieces of electroplated Rookwood.

Interestingly Maria Longworth Nichols Storer had a particular interest in metalwork too. And she produced a collection of metalwork items, including metal pitchers, vases, and paperweights between 1897 and 1900 (source).

New Types of Clay

Ceramics are made from three main different types of clay. These are earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain. Early Rookwood pottery is usually classed as being earthenware (source). What makes pottery earthenware is a combination of the ingredients in the clay and the temperature that it is fired at. You can read more about earthenware pottery here.

However, in 1915, Rookwood introduced a new clay body that they had developed which they called Soft Porcelain. This had a whiter body than the earthenware they had used before.

Soft-Paste Porcelain

There are two types of porcelain, hard-paste and soft-paste porcelain. Hard-paste porcelain is referred to as ‘true porcelain’. It is the original porcelain body that contains kaolin, and it was first made in China.

Hard-paste porcelain is very dense, and hard, and it also has the quality of being translucent when held up to the light. True porcelain is fired at 2732F plus (1300C).

Soft-paste porcelain is a later invention. It was created by European ceramicists in an attempt to replicate the elegance of white Chinese porcelain ware. However, soft-paste porcelain doesn’t contain kaolin, the key ingredient of hard-paste porcelain.

Soft-paste porcelain is also fired at lower temperatures, so it is not as hard and is not translucent. The temperature used to fire soft paste porcelain depends on the ingredients used. Frit-based soft-paste porcelain was fired at 2012F (1100C). And soft-paste porcelain containing feldspars was fired up to 2282F (1250C).

In a fascinating interview, Jim Robinson, a glaze chemist at Roodwood observes that to his knowledge, before 1967 Rookwood didn’t fire at temperatures above 2100F (1149C) (source).

So, it’s likely that the soft porcelain used by Rookwood after 1915 was a frit-based recipe fired at earthenware temperatures. Rookwood marked items made with their soft porcelain clay with a ‘P’ sign on the underside of the piece. You can read more about Rookwood pottery marks and how to identify Rookwood here.

Challenging Times

David Rago, of Rago Auctions, states that Rookwood pottery was in its prime around the turn of the century 1898-1910. And certainly, Rookwood suffered as many companies did towards the end of the 1920s (source).

The stock market crash in 1929 and the Great Depression meant that the company was operating in a very different economic climate. In 1932 Rookwood laid off hundreds of workers. The company closed at times and at other times they were working with a skeleton staff.

Rookwood had used molds right from when it had been founded. And in 1904, they started to make Production Ware. These were vases and the like made from molds. They were not decorated or incised by artists, but they were glazed. The glazes were sometimes plain and sometimes speckled.

During the depression, Rookwood produced more of these production pieces. The pieces had lower production costs, and they were more affordable to a wider number of buyers. As a result, they helped the company survive the economic downturn.

However, in 1939 WWII began, and the demand from European buyers for ceramics was interrupted. This is one of the reasons why Rookwood eventually filed for bankruptcy in 1941.

After 1941 Rookwood changed ownership a number of times before being bought by the Herschede clock company in 1959, and in 1960 Rookwood was moved to Starkville, Mississippi. In 1967, only seven years after relocating to Mississippi, Rookwood Pottery ceased production.

The Townley Era

In 1982, 15 years after operations ceased, the Rookwood assets were bought by a Michigan dentist called Arthur Townley. The assets included the trademark, around 2000 molds, original hand-drawn designs, original molds, clay and glaze recipes, technical notes, and memorabilia.

Arthur (Art) Townley and his wife Rita were not potters or artists, but they were ceramic enthusiasts. In order to keep the Rookwood trademark alive, Art and Rita produced a limited number of figurines using the original Rookwood molds.

Although Arthur Townley was not a trained ceramicist, it’s likely that being a dentist would have helped him with the fine craftsmanship involved in making ceramics from a mold. Mark Chervenka, author of Antique Trader Guide to Fakes and Reproductions explains that the Townleys produced around 500 pieces from each mold that they used (source). And they produced about 1000 pieces a year from their workshop.

Townley Rookwood

There were a few differences in how the Townleys made what came to be known as New Rookwood Pottery. Firstly, they used white porcelain clay, rather than the softer Ohio clay, and soft porcelain that had been used in the past.

Secondly, the Townleys didn’t apply the glaze by dipping or spraying it on. Bob Batchelor, in his book on Rookwood Pottery, describes how they applied the glaze by brush. As with many of the earlier Production Ware pieces, the Townley pieces were glazed rather than hand decorated.

An additional difference was the way the Townleys marked the base of their pieces. Ware originally made by Rookwood had pottery marks impressed into the clay on the base of the piece. By contrast, the Townleys etched the dates of production into the glaze using a diamond drill. Also, the dates were written in regular Arabic numbers, rather than Roman numerals.

In 2005, the Townleys sold Rookwood Pottery to a couple of Cincinnati investors. And in 2006 Rookwood moved back to its city of origin.

How is Rookwood Pottery Made Today?

On moving back to Cincinnati, Rookwood moved into a new 88,000 square feet production facility at Race Street in the Over-the-Rhine area of the city. And they remain there to this day.

Some of the production techniques at Rookwood remain the same today as they were in 1880. For example, some of the pottery is made on the potter’s wheel. Skilled potters throw individual one-off pieces. And many of the pieces are made by slip casting into plaster molds.

The molds are made by members of the mold team. Sometimes the original molds that still exist in the Rookwood archives are used as templates. The mold designs are adaptations of the original shapes and have a distinctive Rookwood look. Other molds have entirely new designs.

Tiles and other large flat pieces such as a charcuterie board are made using a ram press. Ram pressing clay involves forming the clay by pressing it between two plaster molds. The clay used in the ram press is relatively stiff. It contains about 15% water, which is much less than the 25% water content in clay that is used for wheel throwing.

The ram press at Rookwood is a large 90-ton press that flattens the clay into the required form with its weight.

Modern Rookwood Decoration

In the past, Roodwood was known for its intricate hand-painted designs. Today there has been a move away from painting with underglaze and slip.

The focus now for decoration is the application of glazes sometimes on incised surfaces. The glazes at Rookwood continue to be created by glaze chemists employed by the company.

In the interview mentioned above Jim Robinson, describes how still uses the original Rookwood glaze recipes as a point of reference when he is designing new glazes. These recipes are kept in a cardboard box on file cards. He can reach for them for information and inspiration.

Through a process of testing and experimentation, he creates test tiles with glazes. These test tiles include a wide range of colors and are used like color swatches. The designers and ceramicists at Rookwood then use these test tiles to inform how their vision of how a piece of ware will look.

It is a collaborative process, and the designers will ask if glaze colors can be adjusted to suit their needs.

The Firing Process

Rookwood ceramics are fired in electric kilns today. Electric kilns are cleaner, more efficient, and less labor-intensive than older fuel-burning kilns.

The firing process still happens in two stages, with the pots being bisque fired first and then glaze fired afterward. However, they are now glaze fired at temperatures between 2165-2195F (1185-1200C), which are stoneware temperatures. This is hotter than the original earthenware temperatures used in the original kilns at Eastern Avenue and Mount Adams.

Final Thoughts

Rookwood pottery has been made for over 100 years. Of course, production processes change over so many years. But what’s striking about Rookwood is how much of the original processes remain in place today.

Styles and tastes change, but it’s fascinating to know that many of the original Rookwood designs, molds, and ceramic recipes are still used as a reference today. What’s more, they offer tours of the production facility. So, if you’re ever in the neighborhood you can see how Rookwood pottery is made first hand.