Your cart is currently empty!

The History of Rookwood Pottery – An Extraordinary Tale

Published:

Last Updated:

Affiliate Disclaimer

As an affiliate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases. We get commissions for purchases made through links on this website from Amazon and other third parties.

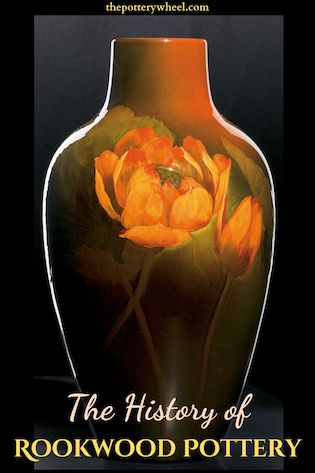

Rookwood pottery is one of the most famous and well-respected brands of American pottery. The history of Rookwood pottery is a captivating and dramatic story. With Rookwood pottery still being produced today, the fascinating story continues to unfold. Here are some of the highs and lows of Rookwood since its inception.

The History of Rookwood Pottery

Rookwood pottery began in 1880, in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was founded by a local female ceramic artist Maria Longworth Nichols Storer. Maria (pronounced Ma-rye-ah), was just 31 years old when she opened Rookwood.

Looking back at that time from today’s perspective, it’s hard to imagine what an incredible accomplishment this was for a woman. In 1880, women had few options and little freedom. It was only in 1920 that women were finally allowed to vote, and Rookwood was started a good 40 years before.

Maria made history when she opened Rookwood Pottery. She was the first woman in the US to found a manufacturing company. Other businesswomen had run companies before. But usually, this was when their husbands, who had run companies, had died and the women had inherited the company. Maria was the first woman pioneer to start her own company.

Maria’s Inspiration

Maria was a keen and talented potter. She worked for a couple of years at a ceramics company in Cincinnati called the Dallas Pottery. This was named after its owner Frederick Dallas. Her time at Dallas pottery served much like an apprenticeship and she learned a lot about decorating techniques and firing clay.

It’s worth mentioning that at the time pottery was a popular pastime amongst women who were quite well off. Their enjoyment of ceramics was often seen as being a distraction from the boredom and narrowness of their day-to-day lives. As such, women expressing an interest in pottery were often looked upon with some contempt.

Maria came from a wealthy family. Her father, Joseph Longworth was a wealthy lawyer and real estate investor. He was also an art collector and a patron of local arts organizations such as the Cincinnati Art School.

As such, it’s likely that Maria didn’t need to work. But she had a passion for ceramics and this motivated her to work and learn about the craft.

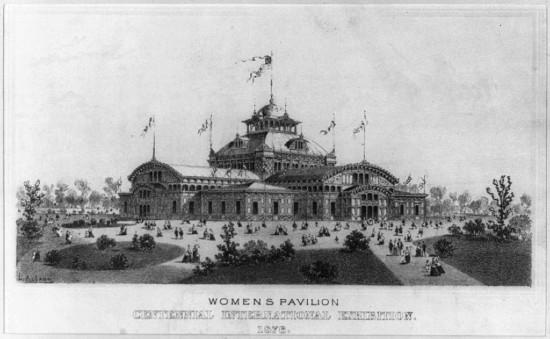

1876 marked a turning point for Maria. She attended the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. This was the 100-year celebration of American independence. Maria entered some of her china paintings in the Women’s Pavilion at the exhibition.

But her imagination was captured by the Japanese and European (particularly French) ceramics that she saw at the exhibition. She was inspired by these entries.

At the time American ceramics was not held in particularly high esteem internationally. Maria decided that she wanted to change this. She wanted to create a pottery movement that would rival the Japanese and European ceramics she had seen at the Philadelphia Exhibition.

Maria’s Personal qualities

Maria was a trailblazer. She had a unique combination of qualities that acted as a mobilizing force in the history of Rookwood pottery. As mentioned above, she was a talented ceramic artist.

But in addition to this, she was ambitious and dogged. Rather than being intimidated by the other entries at the Philadelphia Exhibition, she used her admiration as a motivator to launch her own business.

Remarkably, she had the conviction to set her sights on making ceramics that would surpass the Japanese and European competition.

She also had a good business head on her shoulders. In addition to having a creative vision, she was able to make good business decisions.

Funding

However, artistic ability and business acumen alone were not enough to start a business. The reality is that Maria needed funding and in the beginning, the money that supported Rookwood came from her father’s financial support.

Joseph Longworth is said to have invested a considerable amount of money in Rookwood pottery in its early days.

The Early History of Rookwood Pottery

Maria opened the first kiln in a small factory on Eastern Avenue in Cincinnati on Thanksgiving day in 1880. She had the help of two teenage workers.

It was shortly after that kiln opening that she named the pottery factory, Rookwood. This was the beginning of the history of Rookwood Pottery. The factory was named after the estate owned by her father which was her family home.

See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Part of Maria’s talents seems to have been knowing who and when to turn to for advice and expertise when it was needed.

During the time when she was setting up Rookwood, she took advice from Joseph Bailey who worked at Dallas pottery. He advised her about what kilns and equipment to buy, and firing techniques.

Also in 1883, she brought a business partner William Taylor Watts on board, to help her grow the pottery.

She also hired skilled potters, decorators, and glaze technicians to develop new lines of pottery with distinctive glazes.

From the time that the pottery opened, Rookwood produced individual pieces of pottery that were wheel thrown and hand decorated. They also made production pieces that were cast in plaster molds. You can read more about how Rookwood Pottery was made here.

Making pottery using molds was partly a business-savvy decision. But it was also motivated by Maria’s desire to make pottery that was accessible to more people. She wanted to make beautiful pottery available at an affordable price.

Her aspiration was to create lovely art that would bring aesthetic joy and improve people’s homes. She called this Art Pottery.

American Art Pottery

Rookwood was one of a number of potteries that are referred to as American Art Pottery. American Art Pottery emerged in the US around the same time as the Arts and Crafts movement was underway in the UK and Europe. you

American Art Pottery and Arts and Crafts shared a similar aim of wanting to revive handcrafted ware. The Arts and Crafts movement started in the UK in 1860. It evolved in response to a growing concern that industrialization was having an unwanted effect on the day-to-day life of workers.

There was also a concern that the objects made using mass-production techniques were of poor quality. The Arts and Crafts movement wanted a return to individually crafted ware, produced by skilled artisans.

The American Art Pottery movement which began around 1870 and stretched to 1950 shared these values.

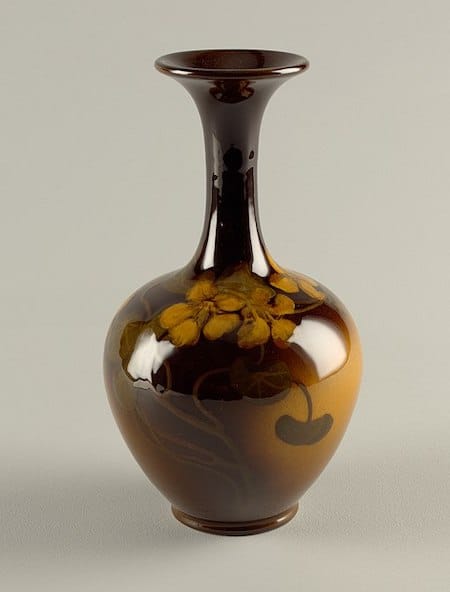

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Rookwood is one of the potteries that form the history of the American Art Pottery movement. Some of the other potteries included:

- Grueby Faience Pottery

- Marblehead Pottery

- Newcomb Pottery

- Roseville Pottery

- Teco Pottery

- Van Briggle Pottery

- Weller Pottery

Rookwood was founded earlier than all of the potteries listed above, except for Weller which began in 1972. So, it’s true to say that throughout history Rookwood was a pioneer even amongst its competitors in the American Art Pottery movement.

This was also the time of the Aesthetic Movement in the art world. The focus of this movement was to produce art that was valued for its beauty rather than its function or deeper meaning (source). Like Arts and Crafts and American Art Pottery, it was a reaction against industrialization.

The Grotesque

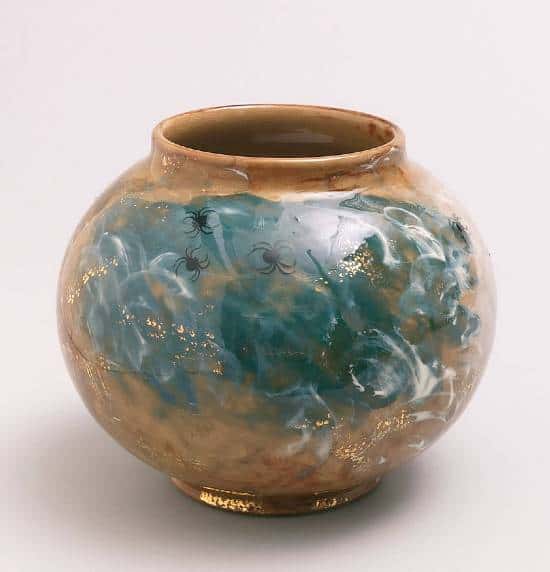

Maria’s hope to bring beauty into people’s homes fits in well with the aims of the Aesthetic Movement. Nevertheless, Maria had a fascination with a style of art that is sometimes called the Grotesque.

The term ‘Grotesque’ has a wide meaning and can be used to refer to different forms of artwork from literature to architecture. In pottery and sculpture, it is sometimes used to refer to intricate designs including mixed animal, human, and plant decorations (source).

Maria enjoyed decorating her pottery with finely rendered images and reliefs of grotesque-style creatures including spiders, crabs, and fish.

Many of the pieces of work produced by Rookwood were individually made on the potter’s wheel. These pieces were then hand painted by the potter and glazed.

The individual potter saw the process of production from beginning to end. Generally, these pieces would be signed on the base by the painter.

However, in tandem with this focus on individual artistic creation, Rookwood also produced batches of pottery from molds. Although these ‘production pieces’ were glazed, they were usually painted with intricate decorative designs. As such, many pieces of Rookwood pottery do not have a painter’s signature on the base.

A Chilly Reception

When Rookwood Pottery opened it was met with a chilly reception from local business people and art critics.

This was partly to do with the fact that Maria was a woman who had dared to set up her own business. In this day and age, it’s hard to imagine how this could be the case. Nevertheless, local business folk felt that it was unseemly and ridiculous for a woman to found her own company.

As a result, Rookwood was met with hostility. It’s also true that at the time it was harder for women artists to be taken seriously. So, Maria had to fight against a tide of opinion that her work was amateurish.

She worked tirelessly with the team that she had assembled. They worked on forms, decorative techniques, and glaze chemistry to perfect their art. And then, within a decade of being opened, the tide of opinion about Rookwood changed.

This change was brought about when Rookwood began to win a series of high-profile competitions.

A Change of Fortune

Rookwood Pottery hired skilled artists to work at their factory. One of the most notable is Kataro Shirayamadani a Japanese ceramics painter. Shirayamadani was working in Boston as a porcelain painter when he met Maria in 1886.

Maria had a long-standing passion for Japanese ceramics, and in 1887 she hired Shiraymadani. He subsequently worked at Rookwood until 1948.

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Not long after that, in 1888, Rookwood entered the Potter and Porcelain Exhibition at the Pennsylvania Museum in Philadephia. Rookwood won two first prizes, one in the category of ‘Pottery, Modeled and Decorated’, and the other for ‘Painting Underglaze’.

This was followed in 1889 by further accolades. Rookwood entered the Exhibition of American Art Industry, again in the Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, and won a gold medal for their Faience work.

Also in 1889, Rookwood achieved international recognition when it came first and won a gold medal at the prestigious Paris Exposition. This was the 10th Exposition Universelle, where the Eiffel tower was showcased. It attracted huge international attention. And as a result, Rookwood pottery came to the attention of the international art scene.

Interestingly, in 1890 Maria gave Rookwood Pottery to William Watts Taylor. He had been running Rookwood in tandem with Maria since 1883. But 6 years later she transferred ownership to Taylor and she stepped back from the day-to-day running of the pottery.

Rookwood Pottery Scales Up

Taylor was a businessman, but he also had a good creative and artistic eye. It was this combination of business drive and creative vision that enabled him to expand Rookwood.

After taking over, Taylor incorporated the pottery and turned it into a business entity. At this point, Rookwood became the Rookwood Pottery Company. Taylor organized for a new pottery factory to be built in Mount Adams. It was larger and had new oil-burning kilns, instead of the older coal-fired kilns used in Eastern Avenue.

The new factory at the Mount Adams site allowed for the business to expand. There was more space to employ more staff and to produce more ware. Rookwood Pottery was scaling up.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A Foray into Faience

After the success of the Paris Exposition, Rookwood wanted to expand its range of ware. They continued to make pottery in the form of vases, dinnerware, ornaments, and the like.

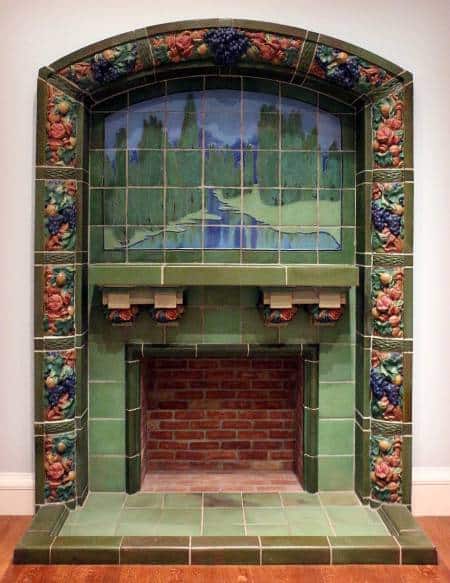

However, they started to move into the area of making ceramic for buildings. This included tiles, mosaics, fire surrounds, plaques, and friezes. Products of this kind are called architectural ceramics, or architectural faience.

The term ‘Faience’ is used to mean a few different things in the world of ceramics. It was a name originally given to ware made in Faenza in Italy. But over the years, it came to be referred to as tin-glazed earthenware.

Tin-glaze gives the otherwise colored earthenware clay a white finish. For example, it was used in the manufacture of Delft pottery in the Netherlands to imitate Chinese porcelain.

Archeologists also use the word faience to refer to glazed pottery in Europe during the Bronze and Iron Ages1. So, faience can mean a number of things.

However, Rookwood came to produce Architectural Faience. This is glazed ceramic ware made from terracotta clay designed to decorate homes and buildings. It was especially fashionable in the late 19th century.

Another Speedy Success

It was around the 1890s when Rookwood started to experiment with making faience. An architectural department was opened at the factory as well as the pottery division.

Their tile work achieved rapid success and in 1903 they won prestigious contracts to provide tiles for several New York subway stations. One example of this is the 23rd Street Subway Station.

They were also commissioned to produce decorative tile work for many other famous buildings in New York. These included Grand Central Station and the Vanderbilt Hotel.

In 1904 Rookwood submitted their tiles to the World’s Fair in St. Louis. This was an enormous exposition and it was here that Rookwoods architectural work came to the attention of a global audience. They won two grand prizes for their tile work.

Some of the architectural installations made by Rookwood have been destroyed. An example of this is the Norse Room at the Fort Pitt Hotel in Pittsburgh. These tiles were designed by John D. Wareham an artist at Rookwood. The tiles included a 9-panel depiction of the poem ‘The Skeleton in Armor’ by Longfellow.

This installation was destroyed in 1967 when the Fort Pitt Hotel was razed to the ground to make way for a redevelopment project (source).

See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Other works by John D. Wareham include this fireplace surround, which was originally installed around a working fireplace in a home. However, it has now been relocated and is on display at the current Rookwood factory.

Sailko, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Surviving Rookwood Pottery Installations

Many lovely Rookwood tiles installations of that era do still exist in their original location and can be viewed today. One of the best-known examples within Cincinnati is the Dixie Terminal Building in Cincinnati.

CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Another example is the art deco Icecream parlor at The Union Terminal in Cincinnati.

Outside Cincinnati, one of the largest Rookwood installations in the world is in Louisville Kentucky. It is the Rathskeller Room at the Seelbach Hilton Hotel.

PEO ACWA, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

You can see Larry Johnson, the hotel historian talking about the Rookwood tiles in the Rathskeller room at the Seelbach Hilton here.

A Fight for Survival

Rookwood had grown from strength to strength in a short space of time. However, times were to change in the late 1920s. The Great Depression began in 1929, and with it, there was a significant downturn in the demand for quality ceramics. Rookwood pottery was about to enter a challenging chapter in it’s history.

The pottery had always had a hand in producing more affordable ceramics for everyday use. And to adapt to the drop in demand during the depression, they increased their manufacture of production pieces.

These pieces were made from molds rather than being hand thrown. And rather than being hand painted or incised, they were given simple glazes to keep the prices down.

This helped Rookwood to survive the depression. However, another blow came in 1939 with the start of World War II. Throughout its history, Rookwood exported a significant amount of pottery to Europe. When Germany invaded Poland, the market in Europe came to a halt.

In 1941 Rookwood filed for bankruptcy. After that, the company changed ownership hands a few times. And in 1959 it was bought by the Herschede Clock Company. This company was in operation from 1885-1984 and they were based in Cincinnati and Starkville Mississippi (source).

It was at this time that Rookwood pottery was relocated to Mississippi. It continued production in Starkville under the ownership of Herschede until 1967 when Rookwood production unfortunately ceased.

A Phoenix from the Kiln Flames

Rookwood was out of operation for over a decade. However, in 1982 a Michigan Dentist called Arthur Townley got wind of the fact that the clock company was planning to sell Rookwood.

It was likely that Rookwood was going to be sold to overseas investors. Townley, who was an avid art collector and lover of Rookwood wanted to prevent this. So, he and his wife invested their savings of around $200,000 to buy the Rookwood trademark, copyright, and assets (source).

Part of these assets included some of the original ceramic molds used by Rookwood. And in 1983 Townley started to make a limited range of pottery using these molds. Some of the Townley-era figurines are still in circulation today. They are usually figurines of ducks, cats, monkeys, or bears.

Image courtesy of Sage Lake Collections

Legend has it that a Cincinnati designer and brand consultant Chris Rose had wanted to buy some Rookwood Union Terminal book ends. He contacted Townley to discuss this. It was on the back of this communication that Chris Rose and his brother Patrick bought Rookwood in 2006 for a reported $1.6 million (source).

The Scripps Family

In 2007 another couple of investors, Martin and Marilyn Wade became part owners of Rookwood. Marilyn (Scripps) Wade is the great-granddaughter of E.W. Scripps who started the E.W. Scripps broadcasting company in 1878. The E.W. Scripps Company has also owned the right to the National Spelling Bee program since 1941.

A new production facility was built in the Over-the-Rhine area of Cincinnati. New equipment was bought, including electric kilns. And new staff were hired to restart production.

In 2011 the Wades become the sole owners of Rookwood. Since then Martin Wade has stepped away from the day-to-day running of the company. And now, with some poetic symmetry, the company is run by Marilyn Scripps, another female businesswoman.

Interestingly, the Scripps family had some history with Rookwood Pottery. Marilyn Scripps’s great aunt Ellen Browning Scripps commissioned a Rookwood pottery artist called Albert Valentien to create a series of botanical paintings. Valentien is a celebrated Rookwood artist, and it was his ceramic decoration that won the gold prize at the Paris Exposition in 1900 (source).

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The commission from Ellen Scripps was to paint all the wildflowers of California. Valentien spent 10 years traveling around California to capture the likeness of the native wildflowers.

Regrettably, the book of paintings wasn’t published at the time, and Valentien died in 1925. However, the enormous collection of paintings was donated in 1933 to the San Diego Natural History Museum by Robert P. Scripps. Since then a selection of the watercolors has been reproduced in a book called Plant Portraits: The California Legacy of A.R.Valentien.

Rookwood Pottery Today

Rookwood Pottery is still operating an 88,000-square-foot pottery factory located on Race Street in Over-the-Rhine. They have a store and they operate tours around their production facility.

As in the past, some of the pieces are made on-site by skilled potters using a pottery wheel. Many of the pieces are made using plaster molds, and for some pieces, a ram press is used.

Importance is also still attached to developing bespoke glazes that are unique to Rookwood. These are created through trial and error by in-house glaze technicians and applied to the pottery by airbrush.

Final Thoughts

Although it’s well over a century since Rookwood was opened, the company is faithful to many of Maria’s original values.

The pottery is designed by skilled Rookwood artists. The pieces are then hand-crafted and decorated. This emphasis on the creative input of skilled artisans links Rookwood today with its forbears in the Arts and Crafts movement and with American Art Pottery.

Marilyn Scripps alludes to this in the forward to Bob Batchelors’ book on the history of Rookwood pottery entitled ‘Rookwood – The Rediscovery and Revival of an American Icon’. She states that “In an era when many organizations aim for authenticity, Rookwood quietly exemplifies it with old-world attention to detail and excellence”.

References

- Hamer and Hamer – The Potter’s Dictionary of Materials and Techniques