Your cart is currently empty!

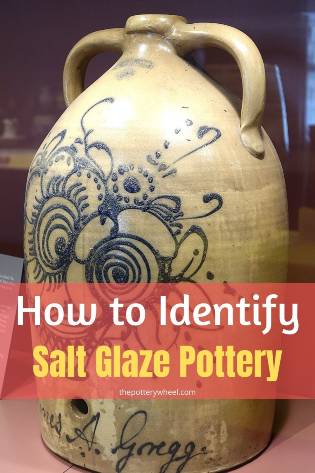

How to Identify Salt Glazed Pottery – Key Features & Marks

Published:

Last Updated:

Affiliate Disclaimer

As an affiliate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases. We get commissions for purchases made through links on this website from Amazon and other third parties.

If you are involved in the pottery field – whether as a potter yourself or lover of fine things – you would have come across quite the number of designs and finishes. From the terra sigillata to salt-glazed pottery, these units bring different things to the table.

Salt-glazed pottery is usually characterized by its German origin. It is also known as vapor glazed, due to the sodium vapors from the salt. This effect brings a high-gloss, translucent appeal to the finished work.

The guide below fleshes out different headings under which you should observe a piece of pottery for whether or not it is salt-glazed.

What is Salt Glazing Anyway?

The salt-glazing process is one of the best, most widely used, and famed adaptations of stoneware production from a few centuries ago. Salt-glazing refers to the heating (to vapor state) of common salt particles during the kiln firing process, causing the salt vapor to bond with the silica (of the clay) and produce a glossy, acid-resistant finish.

The salt is not put into the kiln with the pottery at the initial stages. When the firing process reaches the final, high-temperature region, the salt is introduced to create almost instantaneous vaporization and bonding with the stoneware.

There are two main methods of adding salt to the firing kiln during the production process:

- Using a steel angle – this method employs the direct addition of the solid salt into the kiln. The steel angle is introduced to ensure proper vaporization of the salt before it hits the floor of the kiln

- Spraying the salt solution – it is easy to vaporize the salt in the liquid state, hence this process. The sodium carbonate salt is made into a solution and sprayed into the kiln at the height of its operations.

The Origin of Salt Glazed Pottery

As earlier mentioned, one of the fastest ways to identify salt-glazed pottery is to look for the origin.

If it is German, there is a high chance that the piece was finished using this process.

The salt-glazing process originated in Germany from as far back as the 15th century which informs why it grew to quickly become a staple mode of pottery finishing in the region.

That said, not all German-made pottery is salt-glazed. If it is an old or new piece made in the country, though, there is a high chance that it is.

Numbers and Their Hyphens

Another way to identify German-made pottery, which then translates into salt-glazed items, is by the hyphenated numbers.

It is worthy of note that the earlier pottery to come out of the country did not have any markings on them. Those picks are best identified by other means than with hyphenated numbers.

Whenever you find these numbers, know that you are holding a more modern-day piece of art from the German side.

The first number is indicative of the pottery’s shape while the second number refers to the item’s height (in centimeters).

Marks

Manufacturer’s marks have appeared on different pieces of pottery over time. Salt-glazed pieces are no stranger to the movement. However, they do not all bear the same kinds of marks.

On some units, the marks indicate the manufacturer’s name and also the glazing process. On some other picks, things are not as straightforward.

Leading into the 20th century, manufacturers started stamping their salt-glazed potteries with ink marks on the bottom.

Sometimes, these ink marks show just the name of the manufacturer. At some points, they were combined with the regions where the pottery was made – and some even came with the hyphenated numbers already discussed above.

On Beer Steins

Beer steins found a lot of favor with the potters who made salt glazing their bread and butter.

While you can use the other methods on this list to tell if they were salt glazed or not, the beer steins tended to put a unique spin on things.

For example, the hyphenated numbers usually come stamped/ punched onto the pewter lid of the beer stein. Some of these specific potteries also had special colors added to them with cobalt oxide/ manganese oxide/ iron oxide.

If you can test for any of the above, you will be able to better tell what glazing process was used in the making of the material.

Final Appearance

You would need a keen eye to tell what pottery has been salt glazed.

Here, remember that you don’t need to necessarily see a German marking on the item. While the process was designed and perfected in Germany, it gained widespread acceptance across Europe and America at some point.

That said, the most common colors on the salt-glazed potteries were:

- Rusty brown – a feature of the iron oxide used in the final design process.

- Blue – caused when the cobalt oxide is fired in a kiln. The compound is covered by salt vapor as it evaporates and fuses with the silica content from the clay.

- Orange peel color – the dimpled, high-gloss orange peel color does not occur evenly across the pottery. It is most dominant on the side facing the heat in the kiln and recedes slowly as you spread out to the other sides of the article.

- Purple – this occurs when manganese oxide is the preferred compound for adding design and color to the finished piece.

Final Thoughts

There is a reason why salt-glazed wares – the true ones, that is – cost a premium today.

The manufacturing process goes beyond simply making the pottery/ stoneware and letting it sit in the kiln till it’s done. This time around, the potter has to constantly monitor the temperature of the kiln. They also need to know when to introduce the salt, and how to do that effectively too.

Even at that, the success rate for achieving properly salt-glazed stoneware/ pottery is about 50% or less.

Thus, it is little wonder why you should learn how to properly identify salt-glazed pottery lest you fall scam to one of the poorer reproductions. If you were looking to learn too, a knowledge of how they come about – and what they are supposed to look like as discussed here – should inform the choice of a quality teacher.